How do we know if our son has Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), or maybe both? Where does anxiety fit in? Does this have anything to do with his constipation and other GI symptoms? Our pediatrician seems as confused as we are!

I received this email late one evening and was immediately taken back three years to my own son’s endless doctors’ appointments and school evaluations. He was first diagnosed with anxiety at age four, followed by ADHD at age six.

It took almost three years to finally receive an official diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. We only discovered that he had Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) after we visited a Nurse Practitioner at a local urgent care center for an ear infection.

Our casual discussion raised some red flags for her regarding his digestive issues. Per her recommendation, I made an appointment with a pediatric GI specialist and voila: yet another diagnosis.

It turns out that Autism Spectrum Disorder frequently presents with, and can be masked by, comorbid, or coexisting, diagnoses and disabilities. The numbers are shockingly high: up to 70 percent of kids are managing dual (or more) diagnoses.[1]

ADHD, mood disorders, neurological disorders, and even physical ailments can interact with autism to paint a confusing picture for parents to untangle and understand. Comorbid disorders can delay an autism diagnosis, or be delayed in diagnosis themselves.

It’s a complicated path for parents, doctors, and educators, but even more so for our kids. In this article, we’ll examine some of the most common comorbid disorders and illnesses that impact our autistic children.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

ADHD is a complicated diagnosis on its own. Anxiety and depression frequently accompany it, and understandably so. It takes a lot of tools and strategies to handle a racing brain and impulsivity — more than many kids with ADHD possess — leading to a sort of bottlenecking effect.

Many mental health providers use this term to explain the pileup of thoughts and ideas that occurs when a child with ADHD tries to sort through and process emotions or tasks. Everything gets backed up, like an overflowing funnel. That can lead to intense frustration and strong behaviors.

Now imagine adding the social and sensory components of autism to this. It often escalates the emotional components dramatically.

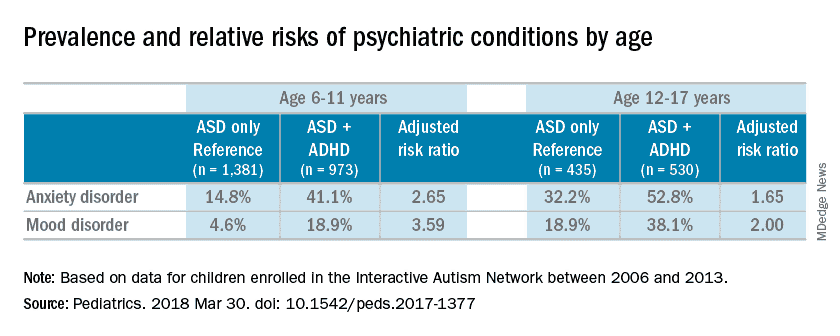

Children with both ADHD and ASD display significantly higher levels of anxiety than children only on the autism spectrum.[2] The contrast between populations can be seen on this chart from Clinical Psychiatry News:

The typical diagnostic symptoms of ADHD, such as distractibility and hyperactivity, are explored in depth in our recent piece by Dr. Ree Langham. These symptoms can snowball for children on the autism spectrum, proving difficult to tease apart.

A child may struggle to wait his turn in conversations, or may interrupt to share information primarily of interest to himself. Is this due to the impulsivity of ADHD? Is this because of a lack of social language skills, characteristic of both ADHD and ASD?

Or is it because of an inability to understand the social norms of conversations, which is primarily an issue of ASD? Or, is it a combination of all of those things?

For example, my son gets extremely excited about Minecraft. (Sound familiar?) He interrupts his dad and I all the time — and I mean all the time — to tell us about his Minecraft ideas. He talks endlessly, almost forgetting to breathe, unless I gently, or not-so-gently, ask him to wrap it up.

He’ll interrupt serious conversations with other adults, barge into a room where his sister is watching a movie, etc., all to share something cool that he just discovered or built in his game.

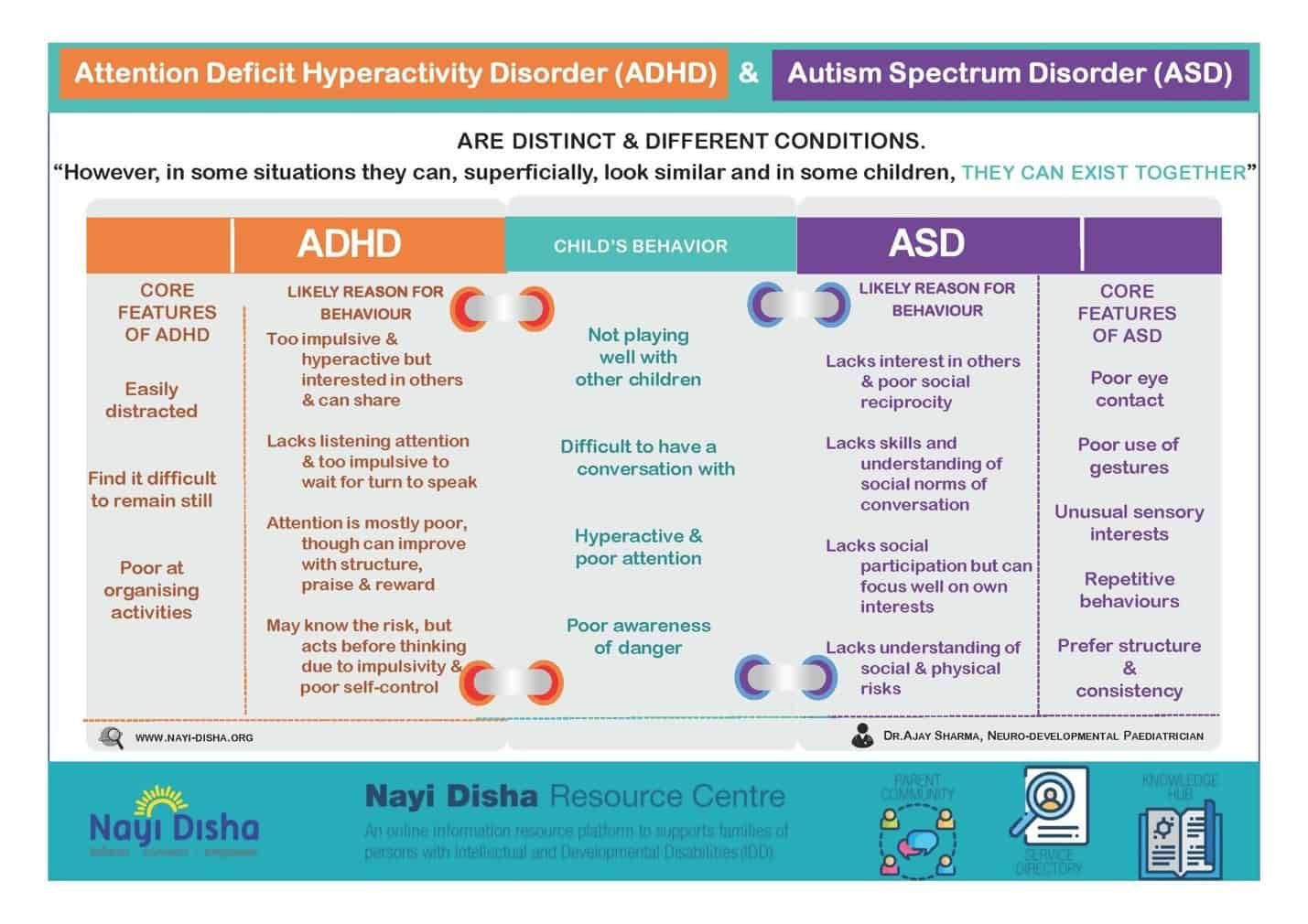

In this diagram from the Nayi Disha Resource Centre, we see some of the overlapping behaviors of ADHD and ASD[3]. Social play, reciprocal conversations, paying attention, and sense of self are all challenges that may arise with both diagnoses.

While most children with ADHD and ASD will not present with all of these behaviors, they usually display several.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for parents of kids with both disorders is how one diagnosis often masks the other. Children with ADHD frequently receive their much-needed ASD diagnosis many years later, preventing both early intervention and the basic understanding that parents, teachers, and doctors need to support and accommodate their kids.[4]

And children with ASD might never get an ADHD diagnosis at all, even with observable executive function and working memory issues. Traditional diagnostic checklists, while useful for data collection, might be less valuable than open conversations and a more flexible understanding of ASD, in general. See our article on atypical autism here.

Mood Disorders

There are many mood disorders that present with ASD: anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, for example.

Autism itself is not defined by mood swings and anxiety, however children on the autism spectrum are significantly more likely to also suffer from one or more mood disorders, which weave in and out of their sensory and social needs to create explosive, overwhelming mood dysregulation at times.

My son’s mood disorder heightens his sensory awareness to painful levels. When he is highly anxious or agitated, a shower feels like needles on his skin. A mild disagreement with his sister becomes a catastrophic event.

The thought of getting on the school bus can lead to sobbing school refusal. Any other day he might shower before I even wake up, make his own lunch, and lose to his sister in an early game of Monopoly without batting an eyelid.

One particular day, my son’s dysregulation took me four hours to decode. He woke up nearly hysterical, both angry and anguished about something he simply could not explain verbally.

I spent the morning soothing him through calm, deliberate redirection. I made him a quick mix of his favorite songs and plugged him into his headphones. We walked to the local donut shop, stopping to throw rocks in the creek along the way.

Any time he started perseverating, focusing obsessively on something upsetting, I would ask him a question about Minecraft (one of the many cool aspects of intense interests). By lunchtime, he was able to type out an email to me describing an event that happened at school the day before.

Thirty minutes later, he walked in the front doors of his school, smiling and ready to tackle science and social studies. His anxiety now soothed, his autistic behaviors settled back into regular patterns. An excited, light stimming movement of fluttering fingers replaced the clear distress of his earlier groaning, forehead punching, and crying.

Autistic needs and behaviors can be heightened by mood, and vice versa. Anxiety is understandable when social interaction is so confusing and the world seems far too loud and brightly-lit.

When others don’t understand your different style of thinking, or worse — they say and do hurtful things to marginalize you further — is it any wonder autistic kids suffer from anxiety and depression?

More complicated mood disorders like bipolar disorder, OCD, and schizophrenia can often display in atypical ways with children on the spectrum, too. Much like ADHD, it can be challenging to distinguish what may be a mood disorder from what is simply the autistic need for less sensory stimulation and specific accommodations.

A child with both ASD and anxiety might be more likely to have severe phobias, obsessions, verbal tics, and struggles related to social interaction. This appears to be much more common with autistic kids who have high cognitive functioning.[5]

This became evident with my son when he turned six. Highly gifted and desperate for friends and acceptance, he plummeted into intense anxiety and depression. He developed a new awareness of his differences compared to his classmates, common in bright kids around ages six to eight.

His anxiety escalated to new heights. He isolated himself more and more, grew depressed, and eventually became suicidal. It wasn’t his autism, specifically, that made him so deeply sad.

But the combination of his autism, his mood disorder, the bullies at school, and the lack of accommodations in his classroom were all too heavy a burden for one six-year-old to shoulder on his own.

I didn’t know what we were dealing with or how to help.

In addition to the high numbers of children diagnosed with ASD and comorbid mood disorders, there are likely a considerable number of autistic children who do not get diagnosed because they either present atypically or, once again, have one disorder masking the other.

Depression and anxiety may display as irritability and/or defiance in a child with ASD. Bipolar disorder may display as a confusing series of mixed-moods, rather than the more traditional manic and depressive episodes.

Autistic children often already struggle with sleep and compulsive talking, so it can be harder to know if those are also signs of mania.[6]

Similar concerns may arise with OCD, Tourette’s, and other mental health disorders.

Self-reporting may be a challenge for children who are either nonverbal or who struggle with language and communication when activated or scared. Anxiety itself can mask or be masked by autism. My six-year-old was diagnosed with selective mutism and generalized anxiety when she was three.

We are now starting the slow-moving, challenging process of figuring out if she is also on the spectrum. Autism and mood disorders can display differently in boys and girls, too, complicating the picture.[7]

Other Disorders

There are several more common neurological and physical disorders that accompany autism diagnoses. Epilepsy, for example, can be found in 20-30 percent of children on the spectrum.[8] While researchers don’t yet know why the two disorders are so frequently dual-presenting, they do know that autistic girls are more likely to have epilepsy than boys.

Doctors have also found that epilepsy is more frequently diagnosed with children who present with more severely-disabling, high-need autism.

Conversely, GI issues like Irritable Bowel Syndrome and reflux, are more common among autistic children and adults that also suffer from anxiety — a mood disorder that presents more frequently among lower-need (sometimes referred to as “higher functioning”) individuals.[9]

While understanding food sensitivities and allergies may play a role in helping to reduce inflammation, reducing stress itself has proven to be a powerful way of helping autistic kids with IBS and/or reflux.

My son took Zantac for years, per his GI specialist’s orders. Once we secured a clearly-defined Individualized Education Program (IEP)[10] at school, with an assistant that helped him take breaks when needed, he weaned off Zantac. His severe heartburn dissipated.

Other areas of physical concern may include migraines, allergies, autoimmune function, and more, all of which may be difficult for an autistic child to verbalize.

It’s important to remember that children with ASD might present in ways that don’t always follow traditional understanding and checklists, so parents often have to dive deeper and search more thoroughly to discover underlying illnesses or medical concerns.

Next Steps

If you think your child might have symptoms of more than one disorder, don’t wait to discuss it with a psychiatrist or psychologist.[11] Many general practitioners do not have the experience needed to tease out overlapping behaviors, but child-focused mental health practitioners can take the time to closely examine what your child is experiencing.

If one doctor or therapist is struggling to hear or understand your concerns, or is less flexible about their diagnosing, then you might need to interview several until you find the right match for your family.

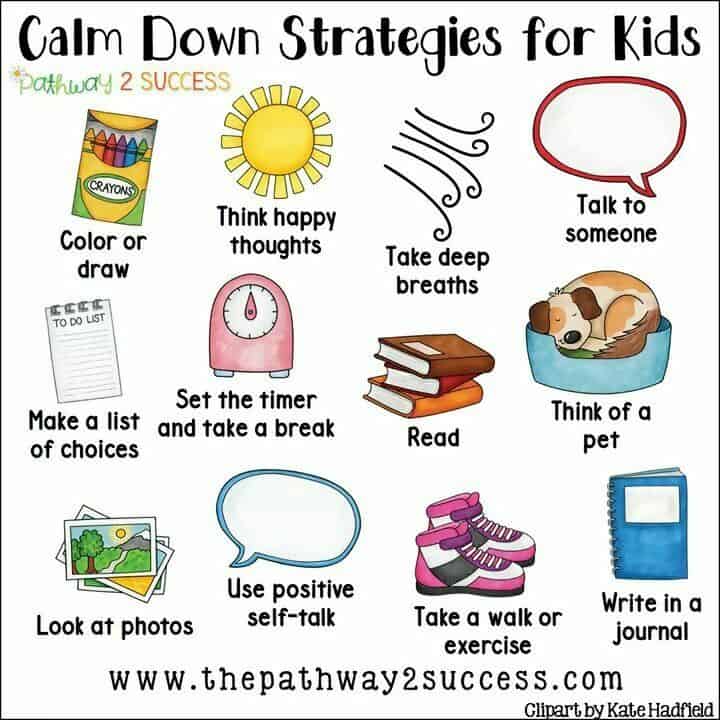

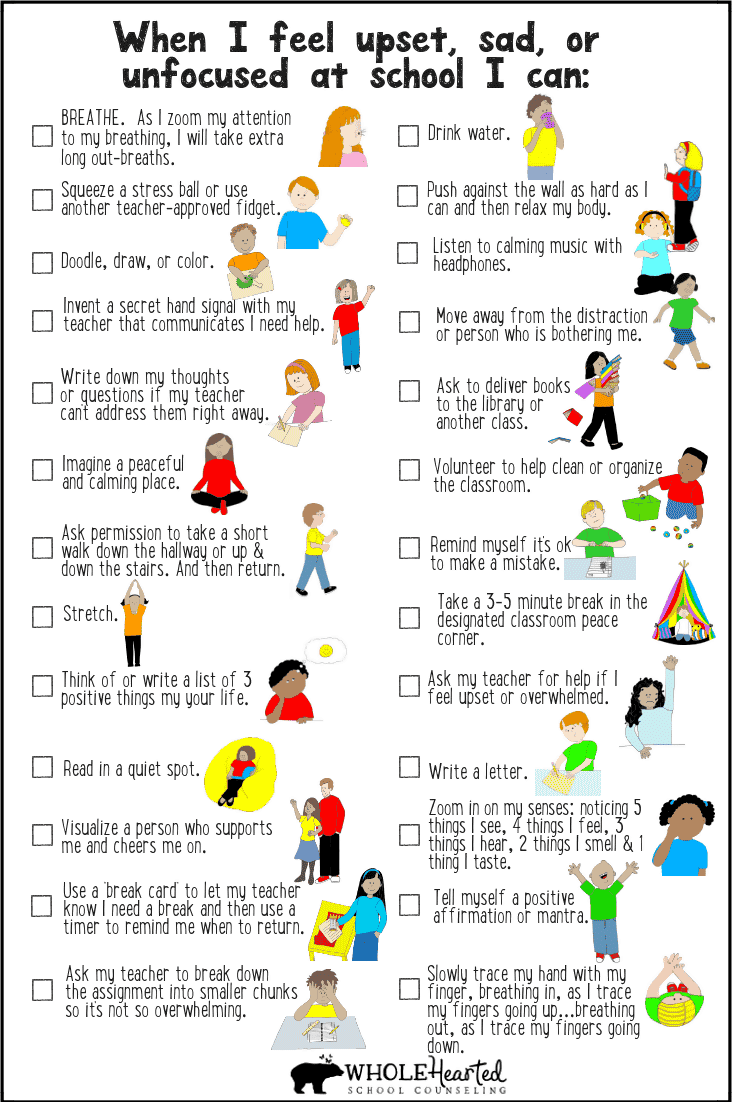

It doesn’t take an immediate diagnosis to support your child now, luckily. Many parenting and teaching strategies can help with anxiety, for example, whatever its root cause. In our home, we use visuals to help our three kids, who all get anxious for different reasons.

At home:

Schools can use 504 plans or IEPs to support children with anxiety. But a lot can be done before that, as well. For example:

It takes time and patience to pinpoint exactly what our kids are going through! More and more doctors and educators are beginning to understand how comorbid diagnoses present, which is good news for all of us.

References

- Merrill, Anna. Anxiety and Autism Spectrum Disorders.

- Colombi, C. and Ghaziuddin, M. (2017, July 25). Neuropsychological Characeristics of Children with Mixed Autism and ADHD.

- https://www.nayi-disha.org/article/autism-spectrum-disorder-asd-attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd-can-they-co-occur

- Roche, Gail. (2018, January 7). Study Explores Why Children With ADHD, ASD Receive Late Autism Diagnosis.

- Merrill, Anna. Anxiety and Autism Spectrum Disorders.

- https://www.autism-help.org/comorbid-bipolar-disorder-autism.htm

- https://ipmh.duke.edu/news/girls-autism-spectrum-are-being-overlooked

- MacGill, Marcus. (2019, January 2). Epilepsy and Autism: Is There a Link?

- https://www.healio.com/gastroenterology/stomach-duodenum/news/online/%7B6c9e6171-0a63-4f1e-9dcb-c7f0dd8e0b59%7D/stress-not-diet-likely-source-of-gi-problems-in-children-with-autism

- https://www.parentcenterhub.org/iep/

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/nurturing-resilience/201011/finding-great-therapist-your-child

This is super helpful–thank you!