“Your son is such a rude boy!”

The assistant principal at my son’s school spoke loudly, her voice piercing through the phone. I found out later that my five-year-old was hiding under her desk, punching himself in the forehead, melting down in pure terror.

Hindsight makes you cringe sometimes.

Nobody knew my son was autistic as a young child, least of all me. He talked in sentences before he was a year old. He hit every milestone early. He loved people, smiled frequently, and was extremely attached to me. Autism never came up at doctors’ appointments or in playgroup conversations.

The normal diagnostic red flags didn’t apply to my son. An example, from myautism.org:

Communication

- Delays in development of spoken language.

- Idiosyncratic repetitive language.

- Lack of pragmatic aspect of language.

- Inability to initiate or maintain language.

- Responds to a question by repeating it, rather than answering it.

- Has difficulty communicating needs or desires.

Social Interaction

- Lack of appropriateness in verbal and non-verbal behavior.

- Lack of ability to develop peer relationships.

- Lack of apparent social and emotion reciprocity.

- Prefers not to be touched, held, or cuddled.

- Has trouble understanding feelings or talking about them.

- Doesn’t share interests or achievements with others (drawings, toys).

Behavior Patterns

- Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior.

- Difficulty in motor control.

- Peculiar attachment to inanimate objects.

- Distressed by a change in routine.

- Lining up toys.

- Head banging.

- Rocking back and forth.

(You can see more at a recent analysis of autism statistics by Blue ABA)

My son spoke early and often, communicating like a much older child. He had many peer friends, though they were predominantly girls who appreciated his sensitive, gentle nature. He was highly empathic, crying if other children were distressed, trying to “fix” any problem a friend had.

He never rocked back and forth, banged his head, or did stereotypical, repetitive actions. It simply never occurred to anyone that he might be autistic.

Looking back, he was much more attached to me than other children his age were to their parents. He exhibited extreme stress when we were separated, beyond the typical separation anxiety that babies and toddlers experience.

No one else could hold him as a baby. He could not tolerate a babysitter, and it took ages for him to connect with and attach to others.

As a two-year-old, his literal language was rather charming and certainly not concerning. Most other two-year-old boys barely spoke! My son would ask for clarification about the words I used.

“I crack you up? What do you mean?” he’d ask, and once I explained, he would use the phrase over and over himself.

His echolalia — the repetition of others’ speech patterns — came through even more clearly in his ability to memorize an entire episode of Blue’s Clues after one viewing. Then repeating it word for word in the car on the way to the grocery store.

My mom friends called him “the little genius.” They loved him. He was unfailingly polite to adults, afraid of displeasing any of us.

“Thank you for the playdate and cookies. I enjoyed this very much,” my two-year-old would say to his friend’s mom as we prepared to go home.

“Oh my. Of course!” she’d gush back, glaring at her own son as he picked his nose and ran around the family room.

Earlier in the playdate, my son had come running to hide behind me. His friend had pointed a toy gun at him and said, “I shot you! You’re dead!” when they dressed up like cowboys.

My son responded, “Why would you want to kill me? I thought we were friends?” and started to cry.

“You’re weird,” his friend answered. And so the pattern began. I didn’t recognize his literal, and limited, understanding of social interactions, so I didn’t help him. I brushed off his worries. I told him to “solve it himself.”

It turns out, I was setting him loose in open water, no swim lessons for training, and no reassurance that I wouldn’t let him drown.

“Swim or sink,” I demanded. So, he learned to swim through those social interactions, but differently — not the four basic strokes, smooth and enjoyable, easily gliding along the surface.

He learned on his own, watching others and mimicking to the best of his ability. Awkward, forceful splashes. Panicked, effort-filled movements. He developed strong muscles and a speedy stroke — but it looked different than everyone else’s swimming. It took more work. It drew the eyes of other swimmers, who would point and whisper.

This is still how he swims through life.

As he attended preschool and then kindergarten, my husband and I became concerned about his anxious behaviors. He’d never had many tantrums, but occasionally would have an extreme meltdown that would last for hours. This changed once he was in school full time.

He had tantrums after school and in the evenings. He was unable to be soothed, and triggered easily and often. He started having nightmares. He begged to stay home and would get hysterical when I dropped him off.

Teachers and administrators dismissed my concerns as helicopter parenting, insisting I trust them and the process.

He began to get bullied in school, even as he quickly learned to read, do advanced math, and prove to be exceptionally gifted. (IQ is defined as 160 or higher is required to be identified as Exceptionally Gifted).

He was identified for gifted services at four years old, the same year he was punched in the stomach by an older boy. The same year he told me he had no friends.

The same year his Montessori teacher told me that if he couldn’t follow the class rules — such as standing quietly in line or eating lunch without covering his ears and groaning — then he couldn’t stay in the program.

Yeah, hindsight makes you cringe sometimes.

We worked our way through anxiety and ADHD diagnoses, but still no one mentioned autism. I found out later that there was a major correlation between ADHD and autism, and that autistic kids with ADHD were frequently delayed in getting their autism diagnosed.

My son just didn’t fit the traditional understanding of autism that the educators and doctors in his life had. He was chatty and enthusiastic, and his inability to follow classroom rules was, according to his school, “demonstrative of a need for stricter behavioral management.”

Basically, they thought he was a bad kid.

It wasn’t until he went into crisis in second grade — his anxiety and depression spiraling into threats of suicide — that we finally got our autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis. And even then, the school wasn’t sure they agreed.

He didn’t get an ASD diagnosis added to his Individualized Education Plan (IEP) until he was nine years old, after a new school psychologist observed him stimming — fluttering his fingers in front of his eyes — during a standardized test and asked to evaluate him.

But calling my son’s autism “atypical” was a copout. Over the past two years of my advocacy work, I’ve met hundreds of autistic kids who were told they were atypical. The problem lies within our understanding of autism, not with the kids who don’t fit into stereotypical neat little boxes.

Redefining “Low” and “High” Functioning Labels: Helping Ourselves and Our Schools Understand Our Kids

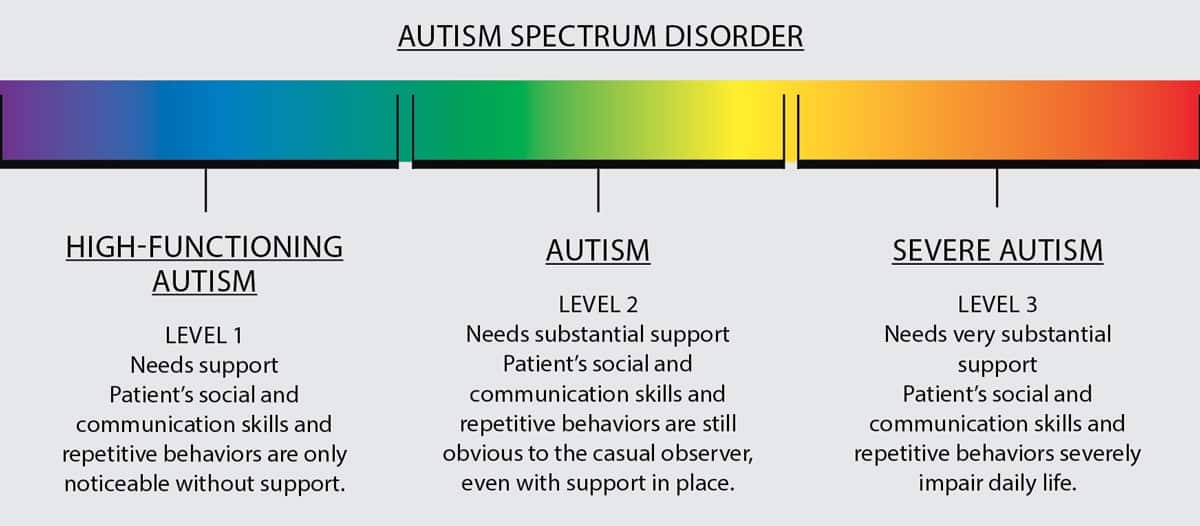

This graphic from Discovery Magazine illustrates how an autism diagnosis is usually categorized, in terms of functionality.[1]

But autism spectrum disorder is not linear, and symptoms and needs tend to cluster in some areas and be nonexistent in others.

A beautiful, approachable description can be found in Rebecca Burgess’ piece in The Art of Autism.

Our kids act different when they’re experiencing stress. When my son gets sick, he is more visibly autistic. When he is worried about something at school, he stims more. When he is having a bad reaction to a medicine, he paces and groans.

The doctor once gave him Ativan for anxiety, and he ran around the house for four hours before collapsing on the ground and sleeping the rest of the day. And don’t get me started on Benadryl…

Research supports our experiences as parents. Reframing these behaviors helps us to understand our children better.[2]

Once the school psychologist evaluated my son, he went from having no ASD diagnosis to having a moderate-severe diagnosis. It was so confusing at first and, to be honest, disheartening.

She noted repetitive stimming and anxiety behaviors. She observed him “get stuck” when he got a math problem wrong, and despite working substantially above grade level, he often punched himself in the forehead and yelled, “I’m so stupid!” At one point during the hour of instruction, he stood up and announced, “I can’t handle this!” and tried to leave the classroom.

The teaching assistant calmly redirected him and he returned to his desk, completing his assignment.

His teachers assured me that on many days he didn’t need much help at all. Then on certain days, he was unable to work and required 1:1 assistance to take breaks, walk around the school, and eat lunch in the classroom instead of the cafeteria.

When he was nervous or agitated, his needs snowballed. When he was calm, he was able to participate in general classroom instruction with his peers.

Over time, he was able to describe this to me as “keeping it together as long as I can.” This is frequently described as “masking” by educators and disability activists. Studies show both positive and negative outcomes of compensation and masking.

Exhaustion and emotional dysregulation, for example, may be daily struggles. Conversely, the ability to mask may help autistic students make neurotypical friends and function more smoothly in the mainstream environment.[3]

Such was the case with my son. He interacted with peers and got straight A’s in school, but would use all of his emotional bandwidth. This would cycle as a period of time with success in school, followed by an increase of visible autistic behaviors, melting down at home, and then, finally, school refusal until he was calm again. Repeat, repeat.

Here is where labeling “high” vs “low” functioning in autism becomes such a problem, and need-based language becomes more supportive and helpful. A student labeled as “high-functioning” might not have his or her needs noticed or met. A student labeled “low-functioning” might not have his or her intelligence or strengths noticed or enriched.

Everything changed for us once our educational team worked with me to reframe my son’s needs. My son is low-need academically, but high-need for self-advocacy. He can do advanced algebra, but cannot ask for a break in an appropriate way.

My son is low-need verbally, but high-need with conversational language. He speaks and writes like an adult, using language to beautifully express his feelings and opinions.

But he interrupts others and struggles to listen and stay on topic in a conversation. Adults modeling and gently redirecting him in social situations helps tremendously.

His mood swings and meltdowns reduced dramatically once his teachers understood and supported this new language and perspective used to describe his differences and needs.

The Keys to Success: Inclusivity, Understanding, and Support in School

With no accommodations in school, autistic kids — even students who seem to be okay behaviorally — end up suffering social isolation, anxiety, poor self-image, and gaps in knowledge.[4]

These issues persist even as some students continue through school with or without a diagnosis. Other students succumb to extreme depression and anxiety, refusing to attend school and/or self-harming or attempting suicide.[5]

Without modeling and tools, these children grow into adults who struggle with adapting to a world that seems harsh and unyielding.

My son had undiagnosed ASD and a comorbid (co-existing) mood disorder. He spiraled into crisis at age seven, becoming suicidal, and was eventually hospitalized at age eight. It took two years to stabilize him and get him back into consistent school attendance.

But with supports at school — with staff who understand and accommodate — the odds for success and emotional health change dramatically. Autistic students with severe intellectual disabilities and/or high-need behaviors can participate in general education classes with the support of special education teachers and assistants.

Lower-need autistic students are often successful with basic accommodations and staff training.

Here are some proven ways that general education teachers can support their lower-need autistic students in the classroom:

- clearly established and ordered routines

- warning and preparation when changes are anticipated

- planning and practicing of communication strategies and social routines

- earplugs or noise-canceling headsets in hallways or lunchroom

- a quiet area where the student can take a time-out, if necessary

- visual schedules and graphic organizers

- visual or written instructions, rather than auditory

- technology use, especially word processing for writing

- a note-taker[6]

Teachers can be trained in Unstuck and On Target, growth mindset,”[7] or a similar method of supporting flexible thinking. They can reframe their understanding of their students’ behavioral challenges, approaching behaviors as evidence of rigidity and/or anxiety, rather than purposeful defiance.

They can learn that this isn’t a bad kid. This is simply a kid who needs support. They can model social stories and gently redirect. Most importantly, they can model inclusivity.

By expecting and demanding both tolerance of and an appreciation for unique learners, they teach all students how to create a classroom environment that is supportive and warm.

Inclusion works. Study after study demonstrates increased test scores and higher levels of empathy and ability to work cooperatively in inclusive classrooms. These findings are not just in the disabled kids, but all kids.

My son is now mainstreamed in a general education fifth grade classroom with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP)[8]that supports his needs.

There is a part-time assistant that supports him and other students throughout the day. He has a quiet room to retreat to when he is stuck and frustrated. His teacher loves him and, over the past few months, his classmates have transitioned from peers to friends.

Recently, he was chosen to be a school ambassador, giving tours to school visitors. He spoke on a panel for parents, explaining his views on autistic students and inclusion in schools. He also won the schoolwide poetry jam, performing his work in front of five hundred students.

He spent the entire winter break asking when he could go back to school.

These are the kinds of sweeping changes and positive outcomes that happen when we reframe and redefine autism based on need, viewing each child as an individual with unique talents and characteristics. This is what inclusion offers when implemented well.

Related Article: How Kids with Autism Think and Learn: A Guide for Parents

References:

- Barna, M. (2017). Everything Worth Knowing About…Autism Spectrum Disorder. Discover Magazine.

- Pruett, J. & Povinelli, D. (2016). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Spectrum or Cluster? Wiley-Blackwell Online Open.

- https://www.neurologyadvisor.com/autism-spectrum-disorder/autism-spectrum-disorder-compensation-clinical-consequences/article/759029/

- Brede, J. et al. (2017). Excluded from school: Autistic students’ experiences of school exclusion and subsequent re-integration into school. Sage Journals.

- Sarris, M. (2018.) The Link Between Autism and Suicide Risk. Interactive Autism Network.

- Retrieved from https://www.washington.edu/accesscomputing/what-are-typical-challenges-and-accommodations-students-aspergers-disorder-and-high-functioning-autism

- https://www.weinfeldeducationgroup.com/uploads/6/5/5/4/6554000/kenworthy.pdf

https://www.mindsetworks.com/science/ - https://www.weareteachers.com/what-is-an-iep/

Great article. This sounds very like our son, who is now diagnosed with Pandas and on long-term treatment.

They don’t differentiate types of autism here in Denmark anymore. It’s viewed as old fashioned & inaccurate because each child has a spectrum of strengths & weaknesses. Originally my son (now 16) was diagnosed with “Intantile Autism”, because he was born with it. His diagnosis is now Autism Plus, because he also has Tourettes Syndrome, which is a common co-morbid syndrome. He would never cope in a mainstream school! He’s in a specialist school. He’s thrived because he’s been educated by highly trained teachers in an environment that has been specially designed to put kids with autism at ease, i.e. no bullying, low lighting, quiet surroundings, individual study booths, use of PECs etc. There are also, on average, 3 teachers to 9 kids in a class! We are extremely blessed here, in that our kids’ schooling is free. Our tax money is put to good use!

Thank you for this

This is remarkable information I am so looking forward to the newsletter that will keep us informed of new advances in autism and also how to relay to our grandson that we love him and know how to respond to him thank you so much for this information

Hannah, this is so on-target & clear & loving. Thank you. It needs to be read by every parent & every educator, teacher & aide. At some point he will write from his own perspective. And we will all continue to learn from the children.