Approximately 30 million people of all ages and genders suffer from an eating disorder in the U.S.

~ National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, Inc.

Written by: Dr Kim Langdon MD

Reviewed by: Dr. RY Langham PhD

Table of Contents

What is Bulimia?

Bulimia nervosa is a set of repetitive behaviors intended to rid the body of the excess calories consumed during eating binges.

These compensatory behaviors include:

- self-induced vomiting

- laxative abuse

- excessive exercise that is joyless or compulsive

- episodes of fasting or strict dieting

- diuretic abuse

- use of appetite suppressant

- failure to use insulin for Type I diabetes, and/or

- the use of medications that speed up metabolism, like thyroid hormones

A person with bulimia may use one or all of these applications to enact this eating disorder.

How is Bulimia Diagnosed?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) uses five key characteristics to classify bulimia nervosa: [1]

- A person with recurrent episodes of binge-eating, or consuming more food than the average person in a 2-hour period, accompanied by a sense of loss of control.

- Repetitive inappropriate behaviors designed to avoid weight gain, such as: excessive exercise, fasting, laxatives, and/or diuretics.

- This eating behavior occurs at least once-a-week for three months.

- Both body shape and weight influence one’s self-evaluation.

- It does not occur concurrently with anorexia nervosa.

Signs and Symptoms

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by the following symptoms: [2, 3, 4]

- General – Dizziness, lightheadedness, and a racing heart due to dehydration

- Gastrointestinal – Throat irritation, abdominal pain (more common among those, who engage in self-induced vomiting), bloody vomit, difficulty swallowing, bloating, flatulence, constipation, Gastric dilation, Barrett’s esophagus, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [5, 6]

- Reproductive – Amenorrhea (lack of menstruation), irregular periods, or light periods. This symptom occurs in approximately 50% of women with bulimia nervosa [19, 20]

- Cardiac – Edema, EKG changes, and an accelerated or delayed pulse rate

- Pulmonary – Aspiration pneumonitis (uncommon)

- Dental Damage

- Enlarged Parotid Glands (jawline)

- Skin –Sudden hair loss, acne, acne, and dry skin

- Hormonal – Low insulin, low thyroid hormone, and low glucose values, low prolactin, and adrenal hormone fluctuations

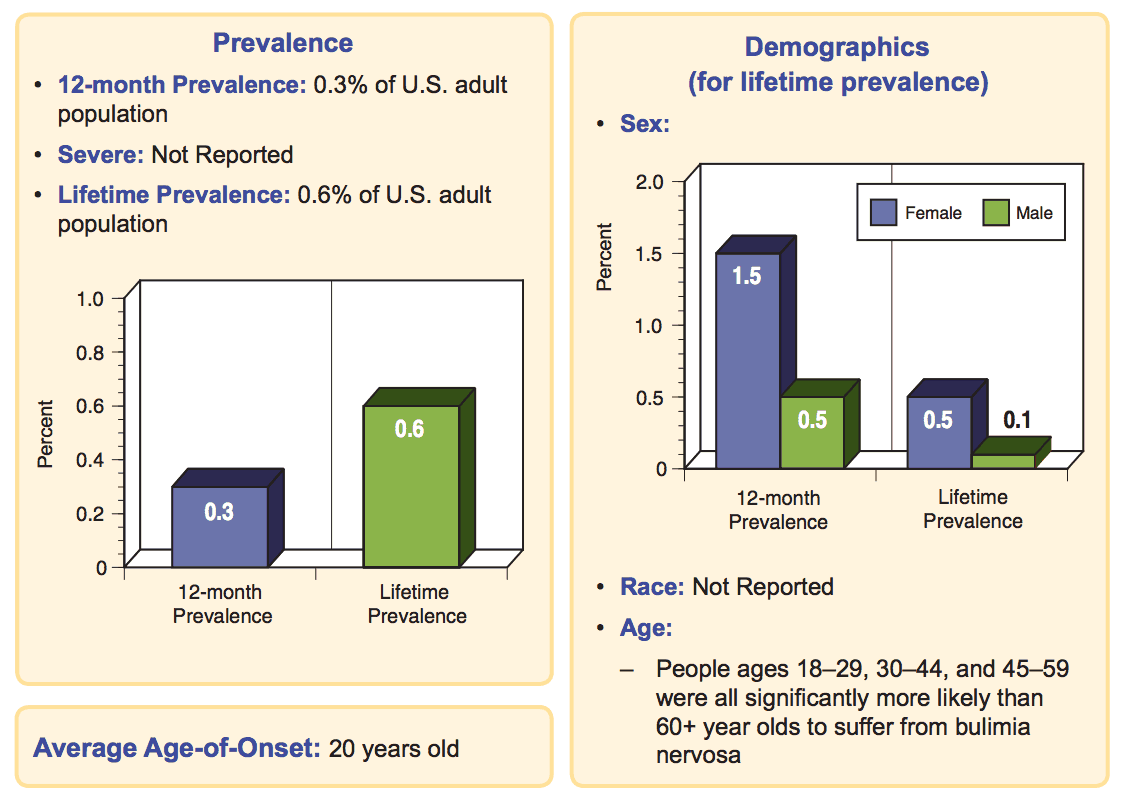

Prevalence

Below are some charts from the National Institute of Mental Health describing the prevalence of Bulimia in the adult population.

Causes

> Neurological [22, 23, 24]

Serotonin is linked to weight regulation and eating behaviors. There have been documented cases of elevated serotonin in the cerebral spinal fluid in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Lower levels of norepinephrine are also associated with anorexia nervosa. Dopamine activity is also linked to body image distortion, and the D4 receptor gene malfunction, which is associated with both bulimia nervosa and binge-eating.

> Hormonal

Hormone changes may be the result or possible cause of bulimia. There are complex irregular interactions between neuropeptide Y (NP-Y), peptide Y (PYY), and anorexia-causing factors such as cholecystokinin (CCK) and beta-endorphin. Furthermore, people with bulimia nervosa have reduced beta-endorphin and CCK levels.

> Genetics

No definite inheritance patterns have been identified in bulimia, but a familial component appears to be involved in the development of eating disorders. There have been proposed genetic links on chromosomes 1, 3, and 10p related to bulimia nervosa. Chromosome 10p may also be linked to obesity, in addition to bulimia nervosa.

In addition, suppression of cholecystokinin (CCK) and ghrelin, following meals may occur in individuals, suffering from bulimia nervosa. Therefore, researchers believe that this predisposing factor could lead to an impaired sense of satiety (sense of fullness) and/or the emergence of an eating disorder. [25]

> Developmental Factors

Developmental factors that could lead to bulimia include: childhood and/or separation anxiety. [26] It also involves a history of childhood trauma and neglect, including subtle degrees of psychological abuse, teasing, and other interactions that generate self-doubt also appear to play a role in the development of bulimia nervosa.

> Sociocultural Factors

Potential precipitating events that can trigger binge/purge eating cycles are: increased anxiety, emotional tension, boredom, environmental food triggers, alcohol use, substance abuse, and fatigue.

Moreover, people, who severely restrict their food intakes, may experience sudden and intense eating binges (in an “all or none” fashion).

Furthermore, both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa sufferers experience intense concerns about weight and appearance.

> Psychological Factors

Self-esteem, self-control issues, impulsivity, perfectionism, body image distortion, susceptibility to triggers, centered on dieting and weight loss, and poor coping skills are all associated with bulimia.

Risk Factors

Bulimia nervosa is more common among people, whose occupations or hobbies requires rapid weight loss or weight gain, such as with wrestlers and competitive bodybuilders. [12] In addition, athletes like track runners and gymnasts are more prone to eating disorders, than athletes like golfers or tennis players. [13]

For instance, a female athlete, who suffers from three or more eating disorders, hypothalamic amenorrhea (a lack of menstrual cycles and/or anovulation – absent ovulations), and osteoporosis, becomes well-known – mostly because in her occupation, slim bodies are of great importance.

Moreover, female gymnasts, divers, long distance runners, and figure skaters have a higher risk of developing eating disorders, partly due to their occupations. It is important to note that male athletes like wrestlers, cyclists, weightlifters also experience eating disorders. Furthermore, actors/actresses, models, and ballet dancers have a higher risk of developing anorexia or bulimia, than those in careers that do not focus on body shape and appearance. [14]

Complications

> Psychiatric complications

Studies indicate that patients with bulimia nervosa have a higher risk of developing major depressive disorder, substance abuse, anxiety disorders, bipolar II disorder, and experiencing sexual abuse.

In addition, mortality from suicide and morbidity associated with depression and poor impulse control – i.e. substance abuse, sexually-transmitted diseases, unintended pregnancies, and accidental injuries can all contribute to the development of eating disorders like bulimia.

Lastly, those with bulimia nervosa, depression, and an alcohol dependency have a very high risk of suicide, especially in those, who excessively exercise. [10, 11]

> Medical complications

The mortality rate for bulimia nervosa is slightly lower than for anorexia nervosa (3.9% vs 4.0%, respectively. [21]

Rare medical complications can occur, such as: delayed emptying of the stomach and/or stomach/esophageal dilation.

Although these complications are rare, they can be fatal if the stomach or esophagus ruptures. In addition, chronic ipecac can result in an enlarged, malfunctioning heart.

Prevention

Removing the familial focus on physical appearance is the best way to prevent atypical thought processes that put people at-risk of developing eating disorders. In addition, programs that educate young people about healthy nutrition, exercise, and weight loss, while promoting self-esteem can also help prevent bulimia and other eating disorders.

- The National Eating Disorders Association may be able to assist with further information, as well as referrals: 800-931-2237.

- Overeaters Anonymous can also help you determine, if you are at-risk for an eating disorder.

When to Seek Professional Help

Bulimics typically have feelings of guilt, and therefore, are less likely to deny that a problem exists, when interviewed by an understanding professional. In addition, a high suspicion index is required when a young person appears to be depressed or extremely weight-conscious.

> A set of screening questions, such as the SCOFF questionnaire [15], can quickly help determine the need for further in-depth questioning.

The SCOFF questionnaire includes the following 5 questions:

- Do you make yourself “S” ick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- Do you worry you have lost “C” ontrol over how much you eat?

- Have you recently lost more than “O” ne stone (about 14 lbs. or 6.35 kg.) in a 3-month time period?

- Do you believe yourself to be “F” when others say you are too thin?

- Would you say that “F” ood dominates your life?

> The Eating Disorder Screen for Primary Care (ESP) questionnaire is an alternative screening tool that contains the following 5 questions: [16]

- Are you satisfied with your eating patterns?

- Do you ever eat in secret?

- Does your weight affect the way you feel about yourself?

- Do you have a family history of eating disorders?

- Do you currently suffer with, or have you in the past, suffered with an eating disorder?

> The Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) is a self-report screening instrument that patients can complete, in the waiting room, while waiting to see a health care professional. [17]

- A family history of eating disorders, anxiety, mood disorders, and alcohol and/or substance abuse/dependence can heighten the risk of developing bulimia nervosa.

- People with bulimia nervosa are more likely, than others to view their families as conflicted, disorganized, non-cohesive, and non-nurturing. These individuals are also more likely to appear to be angry and submissive to hostile and neglectful parents.

- Families members may tease an individual with bulimic tendencies.[18]

- Careful assessment of the family’s dynamics should be undertaken.

Treatment Options

Initial care for bulimia nervosa is usually provided in outpatient settings. Factors like significant metabolic abnormalities, medical complications, risk of suicide, failed outpatient treatment, and inability to care for self may indicate a need for inpatient services. For guidelines on patient-level-of-care, refer to the APA Practice Guidelines for Eating Disorders. [8]

Interdisciplinary Approach

Bulimia nervosa is best managed using an interdisciplinary approach. A primary care provider, psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and nutritionist/dietitian should be involved in the patient’s care. If the psychiatrist is unskilled in this area, a psychotherapist with expertise in eating disorders should be consulted. A nutritionist/registered dietitian should provide the patient with dietary review and nutritional rehabilitation counseling, and he/she should receive proper dental care.

The goals of treatment are as follows: [7]

- Reduce and, when possible, eliminate binge-eating and purging-eating habits

- Treat the physical complications and restore nutritional health.

- Enhance patients’ motivation to cooperate in the restoration of healthy eating patterns

- Provide education on healthy nutrition and eating patterns.

- Help patients reassess and change core dysfunctional thoughts, attitudes, motives, conflicts, and feelings related to bulimia nervosa.

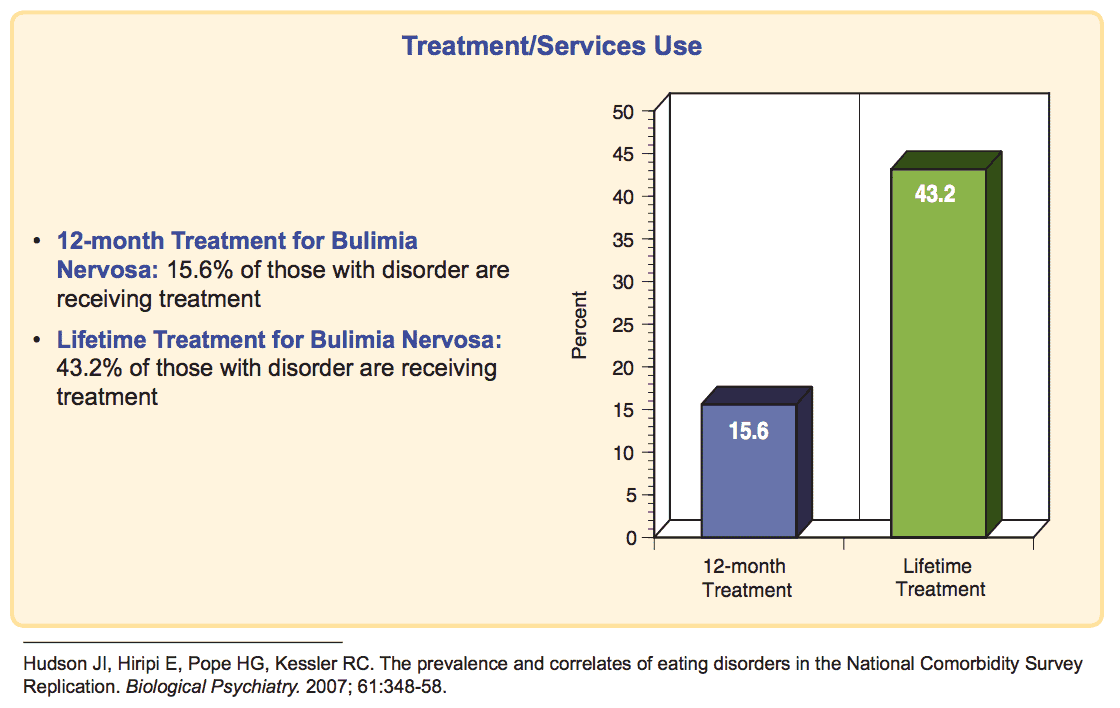

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, only 43.2% of people with the disorder receive treatment.

Outlook

Eating disorders tend to arise within a cultural context that places an extremely high value on “thinness” placing unreasonable expectations on physical appearance.

Awareness of the cultural and social forces, along with education for children and their parents on attitudes and behaviors that foster eating disorders may reduce the occurrence of eating disorders. A family can find learning opportunities through primary care, athletics, and in educational settings.

More so, some schools offer programs that emphasize health, fitness and a wide-range of physical and psychological competences. Research suggests that these programs may reduce the development of the negative attitudes, associated with eating disorders, in vulnerable school-age children. [9] Therefore, experts suggest that the earlier bulimia is recognized and treated, the better the chances for recovery.

Lastly, factors like the length of the symptoms, the age of the individual at the start of treatment, severe weight loss, and/or clinical depression are all associated with a poorer prognosis. The rate of relapse with all eating disorders is fairly high, and usually triggered by social stress. It is important to note that bulimia’s mortality rate is approximately 4-percent.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association DSM-5. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

2. Mehler, P. S., Birmingham L. C., Crow S. J., & Jahraus, J. P. (2010). Medical complications of eating disorders.

3. Grilo, C. M., & Mitchell, J. E. (2010). The treatment of eating disorders: A clinical handbook. New York: The Guilford Press.

4. Brown, C. A., & Mehler, P. S. (2013). Medical complications of self-induced vomiting. Eating Disorder, 21(4), 287-294.

5. Brown, C. A., Mehler, P. S. (2012). Successful “detoxing” from commonly utilized modes of purging in bulimia nervosa. Eating Disorders, 20(4), 312-20.

6. Denholm, M., & Jankowski, J. (2011). Gastroesophageal reflux disease and bulimia nervosa–a review of the literature. Disorders of the Esophagus, 24(2), 79-85.

7. Dessureault, S. & Coppola, D., & Weitzner, M., Powers, P., & Karl, R. C. (2002). Barrett’s esophagus and squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with psychogenic vomiting. Int J Gastrointestinal Cancer, 32(1), 57-61.

8. Shapiro, J. R., Berkman, N. D., Brownley, K. A., Sedway, J. A., Lohr, K. N., &Bulik, C. M. (2007). Bulimia nervosa treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int J Eat Disorders, 40(4), 321-336.

9. Treatment of patients with eating disorders. (2006). American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry, 163(7), 4-54.

10. Haines, J., Sztainer, D., Perry, C. L., et al. (2006). V.I.K. (Very important kids): A school-based program designed to reduce teasing and unhealthy weight-control behaviors. Health Education Research-Theory and Practice, 21(6), 884-895.

11. Brauser, D. (2013). Excessive exercise predicts suicidal behavior in eating disorders. Medscape Medical News.

12. Smith, A. R., Fink, E. L., Anestis, M. D., Ribeiro, J. D., Gordon, K. H., Davis, H., et al. Exercise caution: Over-exercise is associated with suicidality among individuals with disordered eating. Psychiatry Res, 206(2-3), 246-55.

13. Goldfield, G. S., Blouin, A. G., & Woodside, D. B. (2006). Body image, binge eating, and bulimia nervosa in male bodybuilders. Can J Psychiatry, 51(3), 160-8.

14. Johnson, M. D. (1994). Disordered eating in active and athletic women. Clin Sports Medicine, 13(2), 355-69.

15. Ravaldi, C., Vannacci, A., Bolognesi, E., Mancini, S., Faravelli, C., & Ricca, V. (2006). Gender role, eating disorder symptoms, and body image concern in ballet dancers. J Psychosom Res, 61(4), 529-35.

16. Morgan, J. F., Reid, F., & Lacey, J. H. (1999). The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ, 319(7223), 1467-8.

17. Cotton, M. A., Ball, C., & Robinson, P. (2003). Four simple questions can help screen for eating disorders. J Gen Intern Med, 18(1), 53-6.

18. Mintz, L. B., & O’Halloran, M. S. (2000). The eating attitudes test: Validation with DSM-IV eating disorder criteria. J Pers Assess, 74(3), 489-503.

19. Keery, H., Boutelle, K., Vanden Berg, P., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). The impact of appearance-related teasing by family members. J Adolesc Health, 37(2), 120-7.

20. Pinheiro, A., Thornton, L. M., Plotonicov, K. H., et al. (2007). Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disorders, 40(5), 424-34.

21. Pinheiro, A., Thornton, L. M., Plotonicov, K. H., et al. (2007). Patterns of menstrual disturbance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disorders, 40(5), 424-34.

22. Crow, S. J., Peterson, C. B., & Swanson, S. A. (2009). Increased Mortality in Bulimia Nervosa and other Eating Disorders. Am J Psychiatry, 166,1343-1346.

23. Scherag, S., Hebebrand, J., & Hinney, A. (2010). Eating disorders: the current status of molecular genetic research. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 19, 211-226.

24. Kaye, W. Neurobiology of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. (2008). Physiology & Behavior, 94, 121-135.

25. Bailer, U. F., Kaye, W. H. (2003). A review of neuropeptides and neuroendocrine dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. CNS and Neurological Disorders, 2, 53-59.

26. Monteleone, P., & Maj, M. Dysfunctions of leptin, ghrelin, BDNF and endocannabinoids in eating disorders: beyond the homeostatic control of food intake. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38 (3), 312-30.

27. Andersen AE, Yager J. Eating disorders. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2009. pp. 2128–49.

Thanks for sharing this information. Glad you are getting the word out and educating!