Handwriting is a skill that all children must learn before they can effectively communicate their thoughts on paper. Legible handwriting is vital to a child’s success in school. For some children, however, handwriting is a monumental struggle that leaves them exhausted and frustrated and causes them to fall behind in their schoolwork.

Is your child one of these children? If yes, your child may have dysgraphia. This guide will explain what dysgraphia is, how it may affect your child’s education, and what can be done to help your child.

Table of Contents

- What is Dysgraphia and How Is It Diagnosed?

- The Examples of Dysgraphia in This Guide

- Symptoms of Dysgraphia

- What Causes Dysgraphia?

- How Common is Dysgraphia?

- Is Dysgraphia the Same as Dyslexia?

- How Do I Know It’s Not Just Bad Handwriting?

- Is Dysgraphia Associated with Other Conditions?

- Will My Child Outgrow Dysgraphia? What’s the Prognosis?

- How Will Dysgraphia Affect My Child’s Education?

- How is Dysgraphia Treated?

- What Can I Do for My Child at Home?

- Resources for Parents

What is Dysgraphia and How Is It Diagnosed?

Dysgraphia is a learning disability that causes difficulty with handwriting and spelling. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (2013), defines dysgraphia as a learning disability with impairment in written expression.

The manual does not include dysgraphia as a separate diagnosis, but includes it under the diagnostic criteria for Specific Learning Disability (SLD). Because of this, practitioners do not typically diagnose dysgraphia as a separate condition, but will diagnose it as a part of an SLD instead.

When an SLD is not present and a child displays symptoms of dysgraphia but no other condition, then dysgraphia may be diagnosed as a separate disorder, based on symptoms.

If you suspect that your child has dysgraphia, talk to your child’s teacher about a referral for a special education evaluation. It will be important for your child to be tested for all types of learning disorders, not just dysgraphia, in case other conditions are also present.

Your child’s teacher can assist you in obtaining a referral for a special education evaluation. Once this process is started, a school psychologist can evaluate your child for dysgraphia and any other suspected learning disorders.

Your child may also be evaluated by a special education teacher, occupational therapist, and speech and language therapist.

This process can be completed within your public-school district. If you child does not attend public school, you can talk to your child’s doctor about a referral to a licensed psychologist who specializes in evaluation of learning disorders.

The Examples of Dysgraphia in This Guide

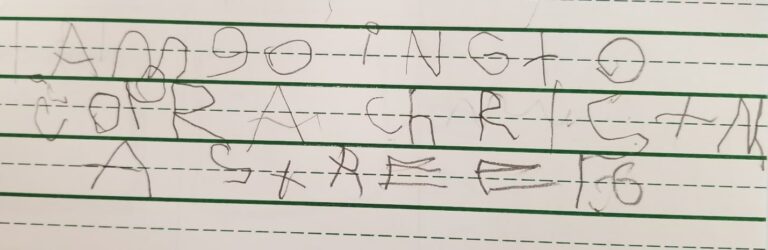

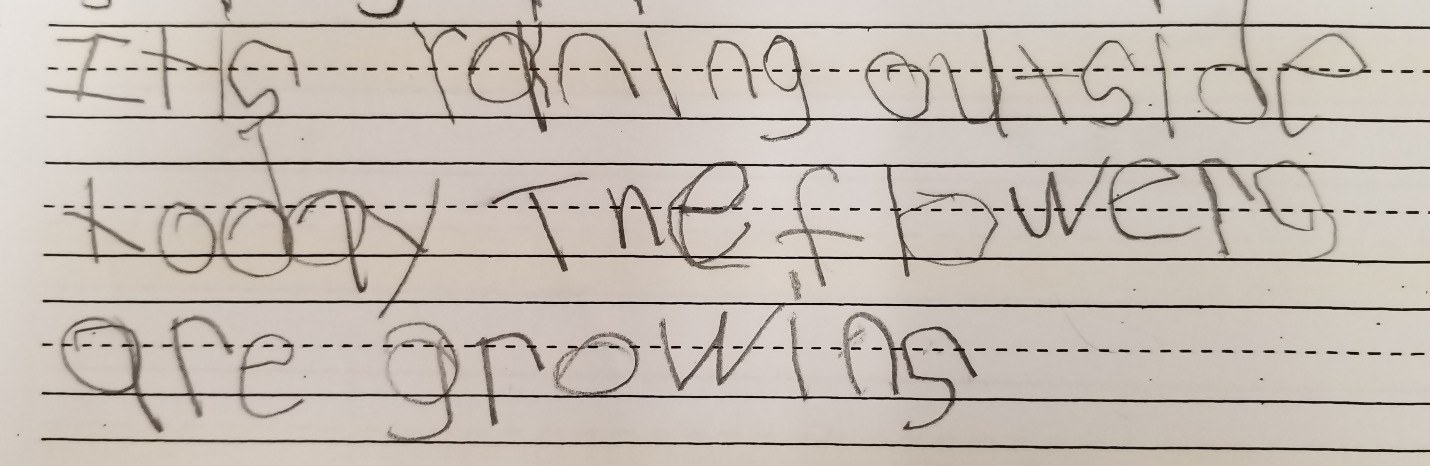

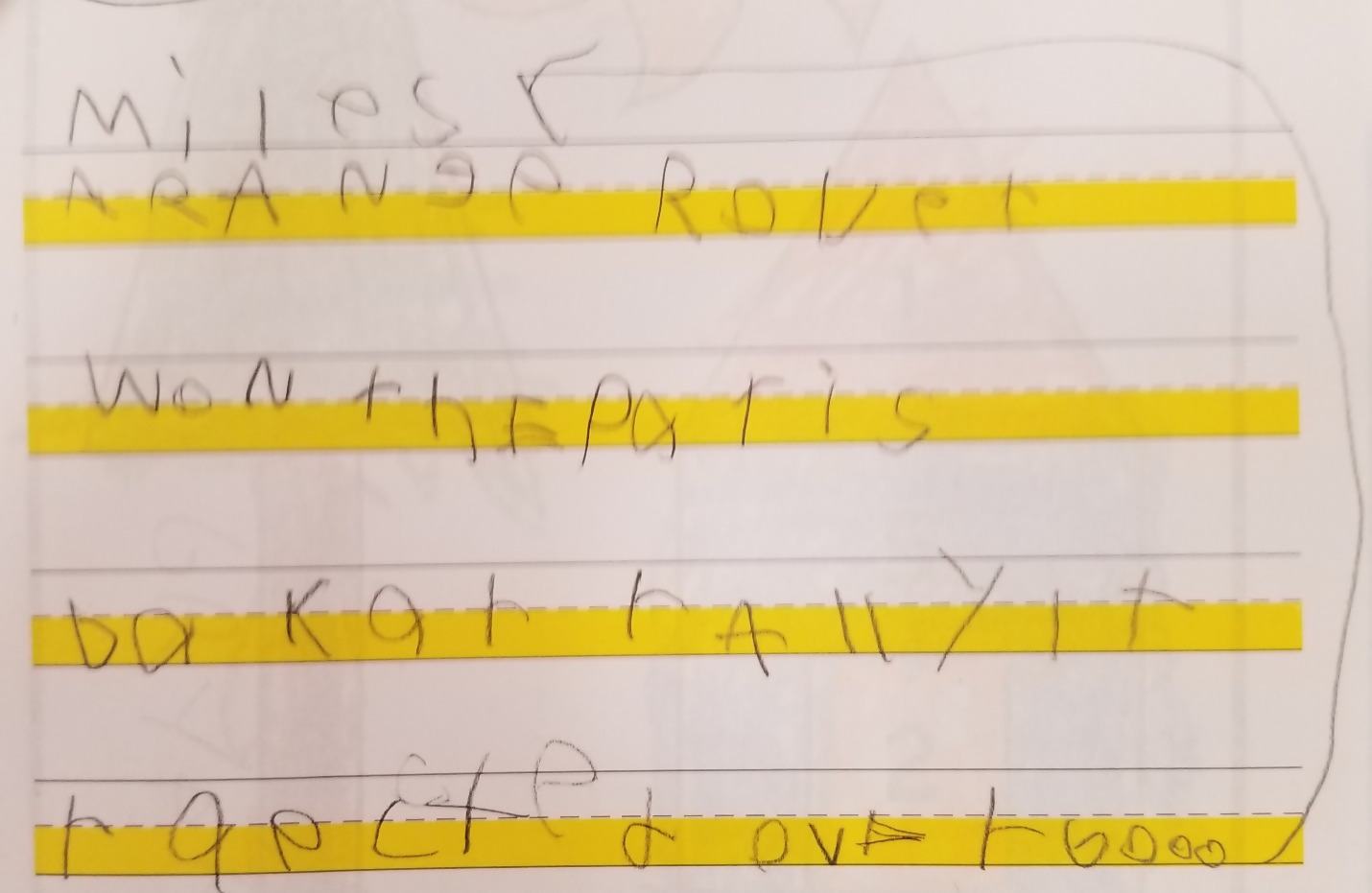

As you are reading this guide, you will notice a few handwriting samples. These are all from assignments completed by elementary school children who have dysgraphia. All of these children also have associated conditions and all are receiving occupational therapy services to address their handwriting.

Notice the problems with spacing, letter formation and letter size and letter alignment in these samples.

Even though the writing in these samples is not what you would expect out of a 2nd or 3rd grade student, keep in mind that the children who produced these samples have worked hard on their writing and it has actually improved with intervention.

This might give you an idea of the extreme difficulty that children with dysgraphia have when they attempt handwriting.

Symptoms of Dysgraphia

Children with dysgraphia may display the following symptoms while writing:

- awkward grasp on the pencil or pen

- letters that are formed incorrectly

- letters that are reversed, upside down, or sideways

- letters and words that are poorly spaced, wither crunched together or spread out too far

- mixed letter case or words written in all upper-case letters

- letters that are not aligned with the writing line

- poor spelling, even when common words are used

- an easier time copying text than thinking of original text to write

- writing sentences or paragraphs that don’t make sense

- taking a long time to write a few lines of text

- complaining about pain or discomfort during writing

- avoidance of writing tasks

What Causes Dysgraphia?

The causes of dysgraphia are unclear, but research has provided some insight regarding why dysgraphia happens.

A study conducted with 3rd and 4th grade children in Germany (Döhla, et. al. 2018) found that children with dysgraphia displayed difficulty listening to and sounding out words, as well as difficulty with the neurological process that the eyes and the brain use to process spatial awareness.

This same study cited prior research that identified dysfunction in the cerebellum of the brain as a possible cause for the difficulty in developing the automatic language, motor and cognitive skills that are required for reading and writing.

Another study (Adi-Japha, et. al. 2007) identified a higher incidence of dysgraphia in children with ADHD, due to deficits in skills not associated with the production of language, such as impaired motor planning and increased pressure on writing tools.

Dysgraphia has also been studied in children with Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) (Chang & Yu, 2010). This study found that children with DCD attained automatic handwriting movements much slower than children without DCD.

While some of these studies associated dysgraphia with other conditions, dysgraphia can occur without an associated condition as well.

How Common is Dysgraphia?

Studies on the prevalence of dysgraphia in the United States are difficult to find due to the fact that dysgraphia often occurs along with other conditions. Those that do exist report that the prevalence of reading and writing disorders together ranges from 7% to 17%.

When dysgraphia is studied as a part of another disorder, prevalence becomes a bit clearer. For example, a study by Mayes, et. al. (2017) examined the prevalence of dysgraphia in over 1000 children ranging in age from 6 to 16 who were diagnosed with either autism or ADHD. The researchers found that 59% of these children had dysgraphia.

Biotteau, et. al. (2019) report that about half of all children diagnosed with DCD also have difficulty with handwriting.

Is Dysgraphia the Same as Dyslexia?

Dyslexia, a condition that impairs a person’s ability to read, and dysgraphia are separate conditions, but they do seem to be closely associated. Impairments in the ability to listen to and sound out words affect both the ability to decode and read words as well as spell words correctly, a skill required for writing.

Children with dyslexia and children with dysgraphia demonstrate some of the same deficits in auditory processing, visual processing, spatial orientation, and the ability of the brain to make motor, cognitive, and language skills automatic (Döhla, et. al., 2018).

How Do I Know It’s Not Just Bad Handwriting?

The simple answer, then, about whether your child has dysgraphia or just bad handwriting, is wait and see. When your child is young, you may not know whether or not your child’s bad handwriting is dysgraphia or just a slight lag behind normal development.

When children first learn to write, they often form letters larger or smaller than normal with incorrect form. Reversals and misalignment of letters on the writing line are common.

With the reduced amount of instructional time allowed for handwriting in public schools today, these problems with handwriting have become more widespread. However, as children get older, they acquire a couple of skills that help them improve their handwriting:

- Children develop the fine motor skills necessary to efficiently manipulate writing tools. These skills are fully developed by about the age of 8.

- As children learn how to read, they become more familiar with how letters and words are supposed to look. This helps children to know when they have committed errors in writing and aids their ability to fix errors. Interestingly, the reverse is also true – children’s ability to write letters correctly aids their ability to read those letters.

The result of this skill development is that handwriting steadily improves for most children until about 3rd grade, when improvement in handwriting levels off. For children with dysgraphia, however, improvements in handwriting can continue past 3rd grade because handwriting skill has not yet been acquired (Overvelde & Hulstijn, 2011).

If your child continues to display problems with handwriting that he or she cannot correct beyond age 9 or 10, dysgraphia is most likely present. You may want to have your child tested for dysgraphia at an earlier age if her handwriting seems abnormally unreadable and if handwriting tasks seem extremely difficult for her.

Is Dysgraphia Associated with Other Conditions?

While dysgraphia can occur on its own, it does frequently occur co-morbidly with other conditions. A few of these conditions have already been mentioned. Here is a list of conditions associated with dysgraphia:

- Dyslexia – not the same as dysgraphia but closely associated, as mentioned above.

- Specific Learning Disability – dysgraphia is often included as a part of this condition, which is usually diagnosed as a specific learning disability in written expression.

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) – children with ADHD frequently have dysgraphia due to their difficulty with spatial attention, working memory, and eye/hand coordination.

- Autism – the visual, auditory, and tactile processing deficits associated with autism contribute to dysgraphia, which is common in children with this diagnosis.

- Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) – decreased hand strength and poor fine motor skills lead to dysgraphia for children with DCD.

- Dyspraxia – children with dyspraxia have difficulty planning actions and carrying them out due to a disorder with the transmission of movement signals between the brain and the body. This results in dysgraphia when children with dyspraxia attempt to write.

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) – damage to the brain can interfere with the processing and movement signals necessary for writing, resulting in dysgraphia.

- Cerebral Palsy – similar to TBI, the damage that has occurred in the brain causes malformation of movement signals between the brain and body, resulting in abnormal movement patterns that interfere with the motions needed for writing. Children with cerebral may also experience some of the same visual, auditory and tactile processing deficits that children with autism experience, further interfering with writing.

Note that these conditions are all neurological in nature, emphasizing that the causes of dysgraphia are centered in the function of the brain and not the result of laziness or lack of instruction in handwriting. These last two situations can be corrected with effort, while neurological problems are usually permanent.

Will My Child Outgrow Dysgraphia? What’s the Prognosis?

Dysgraphia cannot be totally cured. Children with dysgraphia do not “outgrow” it, but can often make improvements in handwriting with intervention and practice.

The reason dysgraphia can’t be cured is that the mechanisms that cause dysgraphia usually persist into adulthood and many people continue to struggle with handwriting even after intervention.

Both children and adults with dysgraphia have to focus so hard on producing handwriting that they cannot devote brain power to what they want to say when they are writing. The overall process can be exhausting.

Children with dysgraphia should learn alternative methods of written communication in addition to handwriting so that their handwriting difficulties will not interfere with their progress in school. This is especially important as children become adolescents and adults and want to consider higher education as a part of their future plans.

Writing is required constantly in high school and college and people with dysgraphia who want their instructors to know what they are writing need to be able to produce that writing legibly and easily.

Since handwriting instruction is not the primary objective in high school and college courses, most adolescents and adults have easy access to the resources they need to produce legible writing.

How Will Dysgraphia Affect My Child’s Education?

If dysgraphia is not addressed early, a child’s struggles with handwriting will adversely affect his or her education. Children with dysgraphia often experience the following:

- Difficulty keeping up with classroom assignments due to slow handwriting speed.

- Difficulty taking notes in classes.

- Illegible assignments that may have to be redone.

- Lower grades than what the children deserve due to poor handwriting.

- Frustration with writing tasks that may develop into a hatred of writing.

- Poor self-esteem and self-image.

Addressing dysgraphia early in a child’s education is important to avoid these consequences as a child progresses through the grades. Due to advances in early intervention, adaptive writing methods, and assistive technology, children should have access to the resources they need to improve or compensate for their handwriting.

In the modern education system, there is really no reason why a child should fall behind due to dysgraphia.

How is Dysgraphia Treated?

When children are learning how to write, dysgraphia can be addressed through multiple strategies to work on the underlying factors causing the dysgraphia. Treatment is usually provided by special education personnel, including special education teachers, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists.

Children with severe spatial deficits may also see a vision therapist. These professionals work with children in the following ways:

Treatment

- Special Education Teachers – Children with dysgraphia may receive special education to help them with deficits in letter identification and sequencing related to spelling and writing down thoughts on paper.Multi-sensory methods may be used to teach skills, including visual, auditory, and tactile input. Children may receive these types of interventions as a part of an overall specially designed language arts program to address a specific learning disability.

- Occupational Therapists – Children displaying symptoms of dysgraphia may be referred to occupational therapy to address the motor and coordination skills required for writing and typing. Occupational therapists provide specialized activity programs for children with dysgraphia that may include the following:

- Exercises to increase core strength to improve posture during writing

- Exercises and activities to strengthen the muscles of the hands.

- Fine motor activities to improve hand coordination, pencil grasp, and pencil manipulation skills

- Eye/hand coordination activities to improve a child’s ability to cross midline and synchronize eye movements with hand movements.

- Spatial orientation activities to help children understand how letters are formed, such as top/middle/bottom motion songs or writing with large motions in the air.

3. Speech and Language Therapists – Children with dysgraphia may receive speech and language therapy to help them process spoken language and translate it into written language.

Therapists may work with children to help them improve the receptive language skills related to processing spoken language, as well as applying those skills to writing down what they hear and sequencing writing so it makes sense.

Adaptations

The above specialists also work with children on adapting writing tasks to compensate for dysgraphia. Adaptation is a large part of the treatment of dysgraphia for a couple of reasons.

- Children with dysgraphia may fall behind in their classes due to the length of time it takes them to complete handwriting tasks and the difficulty their teachers have reading their writing. Adaptations are used to help children keep up in their classes.

- Children with dysgraphia often struggle with handwriting difficulties for their entire lives. Teaching them how to use adaptations early in their education helps them to learn how to compensate for dysgraphia once they reach adolescence and adulthood.

Methods used to compensate for dysgraphia include:

- Adapted writing tools, such as pencil grips, larger pencils or specially shaped pencils to compensate for hand weakness and poor fine motor skills.

- Specialized writing paper, including paper that has highlighted lines or raised lines, that give children extra visual and tactile cues on where to place letters on the paper.

- Manipulatives that allow children to form words without writing, such as letter blocks or stamps.

- Early instruction in typing to compensate for poor fine motor skills.

- Assistive technology to support word and sentence formation during typing. Special typing software programs and apps may provide children with visual and auditory cues to help them know they are typing the correct words.

- Instruction in the use of dictation techniques and voice recognition software so children can speak what they want to write.

What Can I Do for My Child at Home?

Parent support for children with dysgraphia is very important. Parents must learn how to strike a balance between enforcing homework requirements and helping their children adapt to dysgraphia. Here are some things that you can do to help your child, both at home and at school:

Have patience

Your child may not be able to complete a writing assignment quickly. He may need extra time and may need to take breaks at intervals. Don’t pressure your child to get a writing assignment done quickly. You are not a bad parent simply because you are not pushing your child. In fact, a little extra “slack” from you is just what your child needs.

Don’t Be Punitive

Don’t penalize your child for errors in letter formation, letter orientation, alignment, spacing, or poor spelling. Encourage your child to concentrate on his writing and to write as neatly as he is capable of doing, but realize that you may have to lower your standards to allow him to complete a writing task.

It is fine to help your child correct errors but do not give your child consequences for making the errors in the first place. Your child already thinks of handwriting as an unpleasant task and consequences from you will make it even more unpleasant.

Provide Resources

Make sure your child has access to any recommended adaptations or assistive technology at home. Work with your child’s teachers and therapists to gain access to these adaptations so your child has consistent equipment and devices between school and home.

Many schools now use Google for Education, which allows students to access any digital work through their school-based Google accounts.

This makes it very convenient for students to finish their assignments at home, as they can use the home computer to do so. If your child has dysgraphia, it is likely that she has apps and extensions associated with her account that will help her with writing, so make sure she can access these tools at home.

Support Adapted Assignments

Work with your child’s teachers to adapt her assignments. She may need shortened spelling lists, reduced report lengths, or may need to be allowed to type assignments rather than writing them by hand. Teachers are usually willing to adjust assignments for children, especially if the skill being taught is not handwriting.

Some of these adaptations may already be in place at school, so connect with your child’s teacher to find out if any changes are in place. If you child is still expected to complete assignments in the same manner as other children, you may want to have a heart to heart with your child’s teacher.

Follow Through with Home Programs

Help your child to complete any home exercises or activities that are recommended by his occupational or speech therapists. Home programs help children to generalize underlying skills in all environments, so the more your child practices, the better his skills will be both at home and at school.

If you are available, you may want to attend one of your child’s therapy sessions so you can see what types of

this way so that you know for sure when he is completing his home exercises correctly.

Resources for Parents

The following resources may give you ideas on how to help your child deal with dysgraphia:

- Learning Disabilities Association of America – information and resources regarding a wide variety of learning disorders, including dysgraphia.

- LD Online – while primarily a resource for teachers, this website offers parents insight into teaching strategies for learning disabilities, including dysgraphia.

- The Anonymous OT – this easy to read blog offers many posts related to the topic of handwriting.

- OT Mom Learning Activities – many multi-sensory activities are offered here to help children improve handwriting.

- OTs with Apps & Technology – recommendations regarding assistive technology resources for dysgraphia and other learning disabilities can be found here.

Dysgraphia is a condition that can be managed with the appropriate intervention. If you suspect that your child has dysgraphia, talk to the education professionals at your child’s school as soon as possible.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington D.C.: Author.

- Döhla D, Willmes K and Heim S (2018) Cognitive Profiles of Developmental Dysgraphia. Front. Psychol. 9:2006. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02006

- Adi-Japha, E., Landau, Y.E., Frenkel, L., Teicher, M., & Shalev, R. (2007). ADHD and Dysgraphia: Underlying Mechanisms. Cortex, 43, 700-709.

- Chang, S., & Yu, N. (2014). The effect of computer-assisted therapeutic practice for children with handwriting deficit: A comparison with the effect of the traditional sensorimotor approach. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35, 1648–1657.

- Mayes, Susan D., et al. “High Prevalence of Dysgraphia in Elementary Through High School Students With ADHD and Autism.” Journal of Attention Disorders, 25 July 2017, doi:10.1177/1087054717720721.

- Biotteau, Maëlle, et al. “Developmental Coordination Disorder and Dysgraphia: Signs and Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Rehabilitation.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 2019:15, 8 July 2019, pp. 1873–1885., doi:10.2147/ndt.s120514.

- Overvelde, A., & Hulstijn, W. (2011). Handwriting development in grade 2 and grade 3 primary school children with normal, at risk, or dysgraphic characteristics. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(2), 540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.027