According to Sally Saywitz M.D., co-director of the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity and author of the best-selling book Overcoming Dyslexia:

“Dyslexia is an unexpected difficulty in reading for an individual who has the intelligence to be a much better reader. It is most commonly due to a difficulty in phonological processing (the appreciation of individual sounds of spoken language), which affects the ability of an individual to speak, read, spell and often, learn a second language (1).”

For example, it may take an individual with dyslexia multiple steps to read something, when it only takes someone without the disorder one step to read it.

Therefore, the first step in the multi-step reading process of dyslexics is connection. In other words, the first step involves helping the brain identify letters and connect them to sounds. The second step involves organizing the sounds (i.e. putting them in the right order). The third step involves forming sentences, then paragraphs, and making sure they are clear, cohesive, and constructive.(1)

Keep in mind that both dyslexic children and adults have problems matching the letters to the correct sounds that the letters make.

Below is a helpful video that can help you better understand this condition:

Table of Contents

Statistics/Genetics

Dyslexia is the most common learning disability, representing approximately 85% of those with learning disabilities. (1)

Estimates vary, however approximately one-in-five people suffer from the condition.(1) In addition, even though both boys and girls experience dyslexia, boys tend to be diagnosed earlier than their female counterparts – partly because of behavioral problems commonly associated with dyslexia. It is important to note that dyslexia can occur alone or in combination with other learning disabilities.

This condition tends to run in families. In fact, approximately 40% of siblings have dyslexia (i.e. reading issues) and approximately 49% of parents with dyslexic children also have reading problems. Therefore, researchers have suggested that a number of genes are linked to this condition.(3)

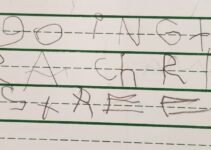

A common myth linked to dyslexia is that people with this condition tend to write their letters and words backwards. The truth is, while dyslexics do tend to write letters and words backwards, so do “healthy” young children – especially when first learning to write. In fact, writing letters and words in reverse is not the most common sign or symptom of dyslexia.(1)

Signs & Symptoms

Although the signs and symptoms of dyslexia are based on the individual, some characteristics have been linked to the condition.

Listed below are common signs and symptoms of dyslexia:(2)

Preschool

• A family history of reading and/or spelling difficulties

• An inability to recognize rhyming patterns like: cat, bat & rat

• Difficulty learning (and remembering) the names of letters

• Constantly talking in “baby talk”

• Mispronouncing familiar words

• An inability to recognize letters in one’s own name

• Trouble learning common nursery rhymes such as “Jack and Jill”

Kindergarten & First Grade

– Differences

• A history of reading problems in parents or siblings

• Complaints about how hard reading is & “disappearing” when it is time to read

• Unable to sound out even simple words like: cat, map, or nap

• Does not understand that words separate in syllables

• Does not associate letters with sounds, such as: the letter “b” with the “b” sound

• Commits reading errors, where there is no connection to the sound on the page. For instance, a person with dyslexia will say “puppy” instead of the written word “dog” – even if a picture of a dog is illustrated on the page

– Strengths

• Has a larger vocabulary than typical for a specific age group

• Has a good understanding of new concepts

• Able to figure things out & get the ‘gist’ of things

• Curious

• Eager to embrace new ideas

• Enjoys solving puzzles

• Has an excellent comprehension of stories

• Has a great imagination

• Has a surprising maturity for one’s age group

Second Grade through High School

– Reading

• Avoids reading out loud

• Doesn’t seem to have a strategy for reading new words

• Has trouble reading unfamiliar words, often making wild guesses, because one cannot sound out the words correctly

• Has delayed reading skills & reads at a slow and awkward pace

– Speaking

• Confuses words that sound alike, for instance mistaking “tornado” for “volcano” & “lotion” for “ocean”

• Mispronouncing long and unfamiliar or complicated words

• Pauses, hesitates, and/or repeatedly says “umm…” when speaking

• Searches for a specific word, but ends up saying “stuff” or “thing” to name an object

• Appears to need extra time to respond to questions

– School & Life

• Has a hard time learning foreign languages

• Has a low self-esteem that may or may not be immediately visible

• Has messy handwriting

• Is a poor speller

• Has trouble remembering dates, names, telephone numbers, and/or lists

• Struggles to finish tests on time

– Strengths

• Able to get the “big picture”

• Has a high level of understanding when something is read to him/her

• Has excellent thinking skills (conceptualization, reasoning, imagination, and abstraction)

• Excels in areas of interest

• Develops a miniature vocabulary that helps one read more fluently in a particular subject area

• Excels in areas independent of reading like in math, technology, visual arts, and/or in more conceptual areas (versus fact-driven) like: philosophy, biology, social studies, neuroscience, and/or creative writing

• Has a surprisingly sophisticated listening vocabulary

• Is able to read and understand material at a high level and over-learn (or highly practice) words in a special area of interest; for example, one with a love of cooking may be able to read food magazines and cookbooks and expertly prepare gourmet meals

Young Adults

– Reading

• Has a history of reading and spelling difficulties

• Has efficient reading skills that have developed over time, however reading still requires great effort and is performed at a slow pace

• Rarely reads for pleasure

• Slowly reads materials (i.e. books, manuals, and/or subtitles in films)

– Speaking

• Avoids saying words that could be mispronounced

• Has a difficult time remembering the names of people and places and/or confuses names that sound alike

• Earlier language difficulties persist, including a lack of fluency and glibness

• Frequently says “umm…” when speaking, and has imprecise language

• Experiences general anxiety, when speaking in front of others

• Often pronounces the names of people and places incorrectly and “trips” over the pronunciation of words

• Rarely has a fast response in conversations and struggles to speak when put on the spot

• Has a smaller spoken vocabulary than a listening vocabulary

• Struggles to retrieve words and frequently has something on the “tip of one’s tongue”

– School & Life

• Despite good grades, believes he/she is “dumb” and/or is overly concerned with what peers think

• Frequently sacrifices his/her social life for studying

• Is penalized by multiple-choice tests

• Poorly performs clerical tasks

• Suffers from extreme fatigue when reading

– Strengths

• Maintains language and reading strengths throughout the school-age years

• Has a high capacity to learn

• Shows noticeable improvement when given additional time on multiple-choice examinations

• Demonstrates excellence when focused on a highly specialized areas, such as in medicine, law, public policy, finance, architecture, and/or basic science

• Has excellent writing skills – if the focus is on content and not spelling

• Is highly articulate when expressing ideas and feelings

• Has an exceptional empathy and warmth

• Is successful in areas that are not dependent on rote memory

• Has a talent for high-level conceptualizations

• Has an ability to develop original insights

• Thinks outside-of-the-box and can see the “big picture”

• Is noticeably resilient and able to adapt

Here is a helpful video that can help you better understand what triggers this condition:

Concurring Conditions

Several learning conditions can concur (co-exist) with dyslexia. Some of these conditions may even resemble dyslexia.

Listed below are other conditions that can co-exist with dyslexia (3):

• ADHD: Approximately 40% of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have dyslexia. People with ADHD tend to have a hard time staying focused while reading. Conversely, people with dyslexia can appear to have problems focusing while reading, when in reality they are grappling with dyslexia – not ADHD.

• Executive Functioning Disorders (EFD): “Executive functioning” refers to flexible thinking, organization, and working memory.

• Slow Processing Speed Conditions (SPS): Slow processing conditions can make it hard to master basic reading skills. Slow processing speed refers to a slower speed of “processing” – i.e. receiving information, analyzing it, and crafting a response to it.

• Auditory Processing Disorders (APD): Auditory processing disorders can affect what a person actually hears. In fact, children with APD tend to have a hard time recognizing different letter sounds and sounding out new words.

• Visual Processing Disorders (VPD): Visual processing disorders can affect what a person actually sees on the page (i.e. words and letters). In other words, words may appear blurry on the page or jump off the page.

• Dysgraphia: Dysgraphia occurs when a person has a hard time writing letters and numbers. In addition, some words may also be difficult to spell.

• Dyscalculia: Dyscalculia occurs when a person has a hard time writing numbers and working math problems.

Dyslexia & the Brain

Brain imaging studies (i.e. functional MRI and PET scans) identify differences between people with and without dyslexia. It is important to note that multiple regions in the brain are responsible for reading.

In addition, the term “neuroplasticity” refers to the concept that the brain is capable of changing. In fact, according to researchers, the brain activity of people with dyslexia can change once they receive proper tutoring.

Here is a helpful video that can help you better understand the relationship between dyslexia and the brain:

Evaluation

A series of tests administered by a reading specialist, clinical psychologist, school psychologist and/or neuropsychologist are used to diagnosis dyslexia. A comprehensive evaluation is used to determine the individual’s strengths and weaknesses. It is also used to identify other learning disorders.

First, the professionals take an in-depth medical and family history, notating previous and/or current learning difficulties. If the individual is a child, the professionals will also examine his/her school reports provided by his/her teacher. (3)

Note: School psychologist can also provide formal evaluations for a child. This can be initiated by providing a written request to school administrators or the child’s principal. School-based exams are free. But, as an alternative, there are private evaluators who charge for their services.

Once the child is tested, an individualized education plan (IEP) or 504 plan may be initiated. This IEP or 504 plan may include specialized reading services and/or classroom accommodations.

Here are helpful videos that can help you better understand the evaluation process:

Treatment

It is important to understand that dyslexia is not a vision problem. Therefore, treatment should not involve eye exercises, vision therapy, tinted lenses, or filters.(5) Rather, the proper treatment should involve learning tools that help decode words and phonics, along with classroom accommodations.

One treatment that can be beneficial for dyslexics is the Orton-Gillingham (OG) technique. The Orton-Gillingham technique is a gold standard dyslexia treatment that involves a multisensory, structured language education (MSLE) intervention. This technique is commonly used by reading specialists, speech-language professionals, and special education teachers to combat learning disorders like dyslexia.

For example, this technique may involve using sandpaper letters to help a person with dyslexia learn phonics.

Or it may involve learning syllables by tapping them out with fingers.

MSLE also includes “over-learning” or learning through repetition.(4)

Classroom accommodations may include: having more time to take tests, having copies of teacher’s notes, having a special seating arrangement, having assisted reading technology (text to speech software or audiobooks), having a classroom attendant, and more.(4)

Below is a helpful video that can help you better understand the Orton-Gillingham technique:

Outlook

There is no cure for dyslexia. It is a lifelong condition. However, early intervention with a reading specialist can improve one’s understanding of the written language, and thus facilitate learning. In addition, classroom accommodations can help those with this condition.

Listed below are helpful resources that can help you better understand dyslexia:

Resources

- International Dyslexia Association

- The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity

- Overcoming Dyxlexia

- Understood for Learning and Attention Issues

References

1. Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity. (2018). What is dyslexia?

2. Understood. (2018). Understanding dyslexia.

3. Understood. (2018). Treatment for kids with dyslexia.

4. American Academy of Pediatrics. (2009). AAP policy: Vision problems do not cause dyslexia.

Great article.

As someone diagnosed at 10 I would not have gotten through school if it had been missed.

I was lucky enough to have a reader/writer for some exams.

What kids need to know is they are smart they just express in a different way. Once someone else helped me write i was on the same level of not higher than some.

Also you mention copies of teachers notes. That helped me as my biggest challenge was tracking on the board and copying it gave me head aches.

Keep up the good work.